Posterolateral Corner Injury

What is it?

Posterolateral corner (PLC) injuries are traumatic knee injuries that are associated with lateral knee instability and usually present with a concomitant cruciate ligament injury.

Source: Ortho Bullets

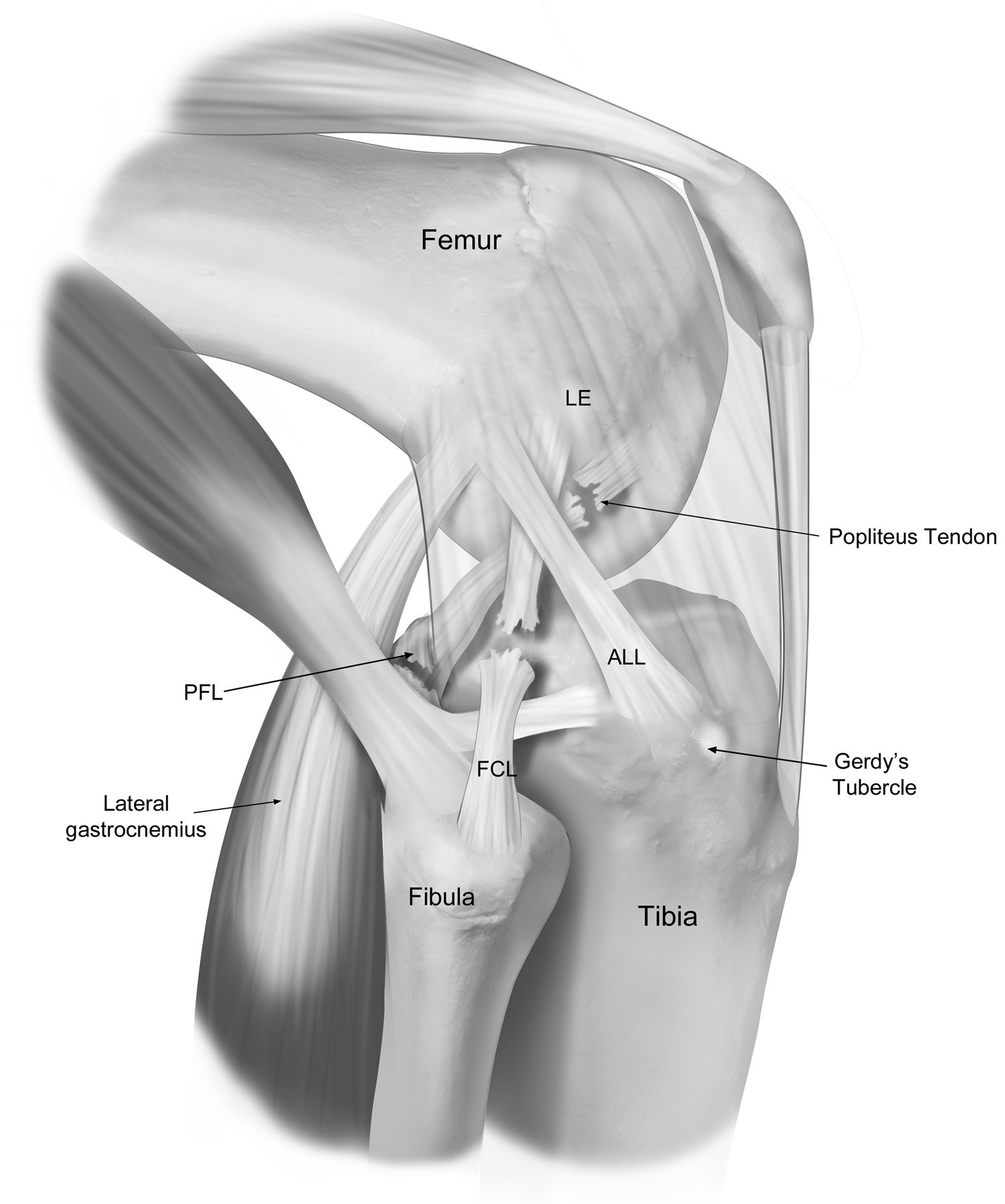

For a long time, the outer structures of the knee weren’t understood. Many surgeons referred to it as the “dark side of the knee” because they didn’t fully understand its importance within the structure of the knee. One of the first things to understand about the outside of the knee, the posterolateral corner (PLC), is that the bony shape is different than the inside of the knee. The tibia and the femur, on the outside or lateral side of the knee where they interact, are both convex in shape, making them unstable. There’s also an important nerve that crosses just below the top of the fibula, known as the peroneal nerve, which can be injured or stretched when there is a PLC injury and can cause a gait abnormality (or foot drop) or nerve pain in the tip of your foot and side of your leg.

How does it get hurt/damaged?

PLC injuries occur in various scenarios. These can include a contact or non-contact hyperextension injury, where the knee bends backwards; from a blow to the inside of the knee while playing sports; or as part of significant trauma such as during a car crash. PLC injuries usually result in the knee gapping to the inside (called vagus gapping), as well as the external rotation of the tibia towards the outside of the femur (called external rotation of the knee). This creates an injury that is highly debilitating and will need to be seen by a medical professional as soon as possible.

How common is a posterolateral corner injury?

PLC injuries are incredibly rare, happening fewer than 5,000 times per year in the US.

When should you be worried about a posterolateral corner injury and what should you do initially?

Due to the complicated structure of the PLC and the injuries that come with it, the need for medical attention immediately after an injury occurs is high. Almost always with a complete PLC injury, some other knee ligament injury accompanies it. The most important is the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), also called the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), which keeps you from swerving side to side. When you experience a significant tear to the FCL, you may not have a lot of swelling or pain in the knee but you may have difficulty moving at speeds faster than a walk and moving to the side of the injury. The other main structures on the outside of the knee are the popliteus tendon and the popliteofibular ligament, both of which make sure the tibia doesn’t rotate externally on the femur.

Due to PLC injuries rarely healing on their own, a timely diagnosis and treatment are essential. If a patient is bowlegged and waits longer than six weeks to be seen by a care provider, then usually that patient will have to have a surgical repair done to bring the bowleggedness into correction before the PLC damage can be attended to. The wait time for the bones to heal can cause an issue for a patient’s long term recovery from the PLC injury.

What is the severity of the injury and the treatment options?

In PLC injuries, due to their rarity and the complex nature of the injury, patients should seek help immediately. For a complete tear of the FCL or the structures in the PLC of the knee, surgery usually should take place within the first two weeks after injury. This creates the best window for the proper recovery process to take place and for the fibers to take hold of the sutures before they break down from enzymes. The knee can also be put in a more normal position during that time frame, rather than when it’s starting to heal in a looser position. Grade 1 or 2 tears can usually be treated non-operatively with physical therapy, but Grade 3 full tears will require surgical approach. As of late, the procedures done for PLC have allowed many patients to get back to high-level activities.

What is my recovery timeline and the anticipated outcome?

Complete PLC injuries when treated acutely (within the first two to three weeks post-injury) with a ligament reconstruction surgery, almost always do better than those that are treated chronically. Patients who don’t have any associated arthritis or cartilage problems can often return to normal activities. Patients with Grade 3 injuries that need to be treated chronically usually do not have a complete return to normal activities.

As for a return to activity, the patient must not bear weight on the injured leg for six weeks after the injury. They then will initiate a partially protected weight-bearing program with crutches at the six week point, and will be able to wean off the weight-bearing assistance implements after they are able to walk without a limp. Driving on the knee that receives surgery will usually be allowed 7-8 weeks postoperatively. Since the majority of these injuries involve other knee ligament issues, the full recovery process can take between 9-12 months.