ACL Tear

What is it?

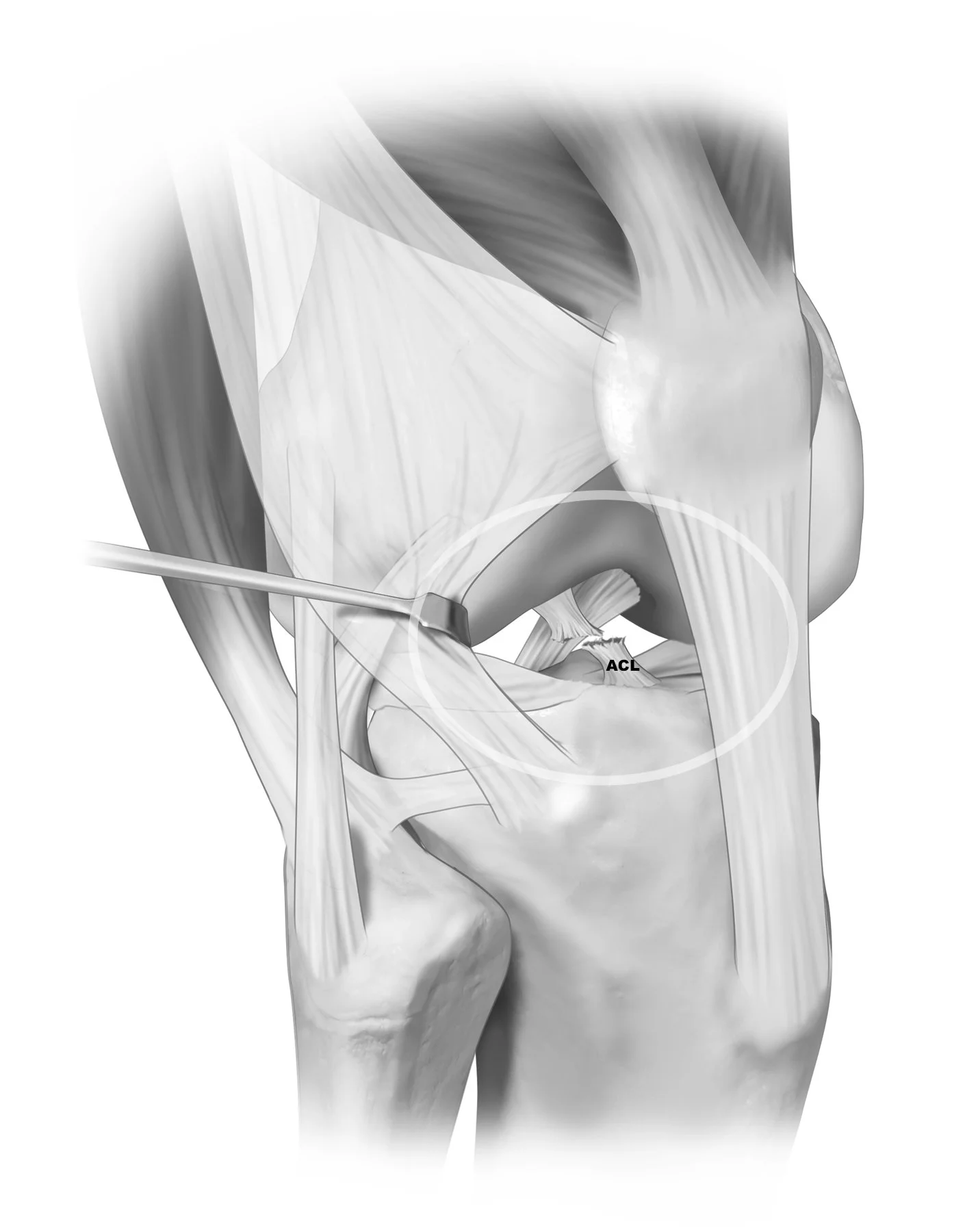

Anterior Cruciate Ligament is an “intra-articular” ligament meaning it is located inside the knee joint. There are two intra-articular ligaments of the knee and two “extra-articular” ligaments that are located outside of the joint. The ACL functions as the primary restraint to anterior (forward) translation (movement) of the tibia. ACL acts as a seatbelt if you will which primarily exerts its action during more high energy or dynamic motions. The ACL also acts as a secondary stabilizer against excessive rotation, namely internal rotation of the tibia.

How does it get hurt/damaged?

The ACL is injured usually in response to significant force, or energy that forces the tibia (shinbone) too far forward. Often times, this is during sporting or athletic events when someone tried to stop abruptly or change direction. Think of a jump stop in basketball, or a juke move by a running back or recover in football. The momentum and energy of the tibia is continuing in a forward direction and the ACL functions as a seatbelt to prevent excess anterior movement. However, excessive anterior translation hen results in an ACL rupture.

Another common way to injure the ACL is a mechanism called the pivot shift. This is a combination of a couple “positions” and forces that act upon the knee simultaneously. The knee falls into a knock kneed (Valgus) position, and simultaneously sustains internal rotation and anterior translational forces. This causes the tibia to be rotated and sublux (move) out the front, thereby tearing the ACL. This is common particularly for younger female athletes during activities like landing for a rebound, or landing from spiking a volleyball.

What are risk factors?

There are a number of both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for sustaining an ACL injury, but to name a few.

Modifiable factors include;

Muscular Strength and Tone. Patients who are more quadriceps dominant are at higher risk. Therefore strengthening programs focues on the hamstrings and gluteal muscles can be very beneficial.

Neuromuscular Coordination. Learning how to properly land, slow down, or change direction all can help minimize the forces that go through the knee.

Sporting Activity. Higher velocity and more dynamic sports are higher risk.

Bodyweight. Higher body weight leads to higher loads through the knee joint and thereby higher forces on your ligaments, cartilage, bones, etc.

Bony Alignment. Patients who are Malaligned tend to be at higher risk of ACL injuries. Namely being knock kneed, or having an increased posterior tibial slope, which is a fancy way of saying the top of your tibia tilts backwards more than average thereby increasing the risk the tibia will translate anteriorly. Of note this is “modifiable” as in it can be corrected, however it requires surgical intervention and is therefore a much bigger task than the others listed above. Bracing can also be utilized however it does not “correct” the issue but helps to minimize risks associated with the malalignment and subsequent overload.

Nonmodifiable

Sex. ACL injuries are more common in younger female athletes. Some of this is due to risk factors previously discussed, female athletes tend to have stronger quadrciceps than hamstrings, and tend to land with their knees in valgus (knock kneed) which both increase ACL risks.

Hypermobility. Double Jointed is a term often used for those patients who can bend their elbows the opposite way, or put their forearms on the ground when bending over to touch their toes. This increased flexibility often comes at a heightened risk for joint instability and ligament tears of the knee due to the body and the knee specifically easily being manipulated into compromising positions.

How common is an ACL injury?

Very common! Approximately 300,000 people tear their ACL per year in the USA.

When should you be worried about an ACL tear and what to do initially?

If you hear or feel a pop, or have a sudden giving way of your knee that is often but not always associated with large knee effusion (swelling in your knee). These are concerning signs.

Ice, and elevate the knee and call to be seen by local doctor/orthopedic surgeon. If you are a young high school/college athlete that has access to an athletic trainer (ATC) go in to see them as soon as you are able. ATCs are incredibly knowledgeable and can help get your workup and treatment started.

Severity of Injury and Treatment options?

ACL injuries are traditionally graded from 1-3, with three being a complete injury. The extent of the ACL injury is important because it can help guide the treatment recommendations of the ACL specifically, however sometimes what is more important is the associated injuries including; the meniscus, the cartilage surfaces, the anterolateral ligament, and other major ligaments and tendons. An isolated ACL is completely different both from a treatment standpoint, as well as a prognostic indicator, than a ACL that has these other associated injuries. This is why It is important not to COMPARE your injury with others. Or another way of saying this is no two ACL injuries are the same, so speak with your medical team, and your family to make sure everyone understand what your injury is and what your treatment options are.

In regards to your ACL specifically (the other injuries are covered in other subsections) there are three main treatment options;

Conservative treatment including physical therapy and bracing. This is largely reserved for patients who have sustained isolated ACL injuries that are either partial tears, or sometimes complete tears in patients who are not interested in returning to high demand, high energy sporting activities.

ACL repair, or to maintain the native acl with sutures, biologic augments and scaffolds to help the ACL heal. This treatment option is gaining traction especially now that we improved techniques and ways to help augment our repairs biologically to help them heal (BEAR Implant). Who is a good repair versus reconstruction candidate is very nuanced and complex topic that is best had with your surgeon, but some aspects most surgeons consider are; a) degree of the tear, b) location of the tear did the ligament tear off its bony attachment, or did it tear in half, c) age of the patient, d) activity level and sport of choice.

ACL reconstruction, or to replace the ACL with a new piece of tissue either from elsewhere in the patient (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). Again, the conversation on what kind of graft/technique is very nuanced, however in general autograft or taking your own tissue is usually considered gold standard. The three main grafts used are; a) patellar tendon, b) quadriceps tendon, c) hamstring tendons.

What is my recovery timeline and the anticipated outcome?

Your rehabilitation timeline is very dependent upon the surgery you undergo, what other concomitant injuries you have, and other patient factors. As an example a patient who has a meniscus root tear, treated concurrently with an ACL tear will likely be nonweightbearing for up to 6 weeks, where a patient with o meniscus tear will potentially be allowed to put weight on their leg immediately. Again important in your recovery journey not to compare yourself to others and stay focused on your treatment and your goals. While the early timeline and checkpoints vary, the final “return to play” ie time to being cleared with no restrictions is likely 9 months to 1 year. The range is again dependent on both patient factors as well as usually on strength numbers and tests performed in physical therapy which allow us to know when your body is ready to return.

In regards to expected outcome, the goal is to get you back to full activity with no restrictions. That means back to scoring touchdowns, goals, shredding fresh powder, or whatever other activities you love.